-

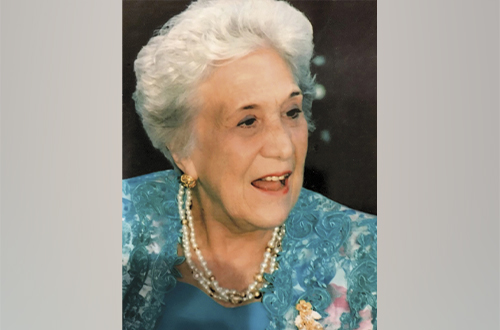

Clarification on Angela Lastrico Raish Scholarship

In the November/December issue of the Notiziario, we reported that the AMHS would administer the Angela Lastrico Raish Scholarship which is separate from and in addition to the two scholarship awards given by the Society each academic year. The source of the funding for the Raish scholarship was incorrectly stated. In fact, the funds for the Angela Lastrico Raish Scholarship are, and will be, from private donations. The Notiziario regrets the error.

January/February 2023

-

Siamo Una Famiglia

A Special Birthday

AMHS Immediate Past President Maria D’Andrea-Yothers was gifted a destination 60th birthday gift from her husband, Sam Yothers, to the beautiful country of Costa Rica. From December 9-16, the couple stayed at the 5-star resort, The Springs Resort & Spa, in Arenal. They enjoyed many excursions and time in the laguna pool and hot springs. Buon compleanno Maria!

At the base of the Arenal Volcano

Credit: Courtesy of Sam Yothers

January/February 2023

-

AMHS Membership

By Lynn Sorbara, 2nd Vice President-Membership

New Members Welcome to our New Members: Tony Andreoli; Dominic & Joanne Balzano; Diana Hoopes; Joseph J. Lese; Sonia Meneghin; Daniel A. Piazza; and Richard Salerni. Birthdays Compleanni a Gennaio

Ventresca, January 2; John Iazzetti, January 4; John Iademarco, January 5; Americo Allegrino, January 8; Judy Damiani, January 11; Abraham Avidor, January 12; Carla DiBlasio, January 17; Henry Lisciotti and Panela Pasquariello, January 21; Bess DiTullio and Karen Kiesner, January 24; and Nonna Noto, January 26.Compleanni a Febbraio

Ventresca, January 2; John Iazzetti, January 4; John Iademarco, January 5; Americo Allegrino, January 8; Judy Damiani, January 11; Abraham Avidor, January 12; Carla DiBlasio, January 17; Henry Lisciotti and Panela Pasquariello, January 21; Bess DiTullio and Karen Kiesner, January 24; and Nonna Noto, January 26.Anniversaries Anniversari a Gennaio

None.Anniversari a Febbraio

Sam & Maria (D’Andrea) Yothers, February 11; Rocco & Yoni Caniglia, February 14; and Michael & Dena DeBonis, February 15.Membership Information Category # of Persons

Associate (Couple): 3 x 2 = 6

Associate (Individual): 40

General (Couple): 51 x 2 = 102

General (Individual): 88

Honorary: 10

Scholarship: 2

Student: 6

Total Membership: 254

January/February 2023

-

AMHS Annual Wine-Tasting coming on Sunday, November 20

By Nancy DeSanti, 1st Vice President-Programs

Credit: Kelsey Knight/Unsplash For a fun autumn afternoon, you should definitely not miss out on our most popular event of the year, our annual wine tasting and luncheon. The event will be held on Sunday, November 20, 2022, at 1:30 p.m. in Casa Italiana. As in past years, members of the Washington Winemakers will be bringing samples of their production to share with the attending AMHS members, friends and guests.

This year, the lunch will be provided by one of everybody’s favorites, 3 Brothers Restaurant.

We owe a big thank-you to Jim Gearing, who is organizing the winemakers’ participation. Based on previous years, there is sure to be a variety of wonderful wines for tasting (and possibly some limoncello or grappa too).

The program will begin with a brief AMHS general meeting at which time we will elect members of the board of directors (please see page 4 for an article by the Nominating Committee about the candidates and the election).

Please make reservations on the Society’s website to make sure you don’t miss out on this fun event. In order to ensure the health and safety of everyone, the number of participants will be limited (first-come, first-served) and vaccination proof will be required. So bring your family members and friends—they will thank you. The deadline for paid reservations is November 17, 2022.

November/December 2022

-

Christmas Tree in St. Peter’s Square Will Come from Abruzzo Forest

By Nancy DeSanti

The central piazza of Rosello, site of fond memories for AMHS Past President Ennio DiTullio.

Credit: Courtesy of Ennio DiTullioThis year, the Vatican Christmas tree in St. Peter’s Square will come from the town of Rosello in Abruzzo’s Chieti province. This was great news for AMHS Past President Ennio DiTullio whose hometown is Rosello and who had just returned from several weeks there when the news broke.

According to Rosello Mayor Alessio Monaco, on December 3, 2022, there will be an audience with Pope Francis in the morning to include delegations donating the Nativity Scene in St. Peter’s Square (from Sutrio, in the province of Udine) and the Christmas Tree (from Rosello). The public ceremony will take place in the afternoon.

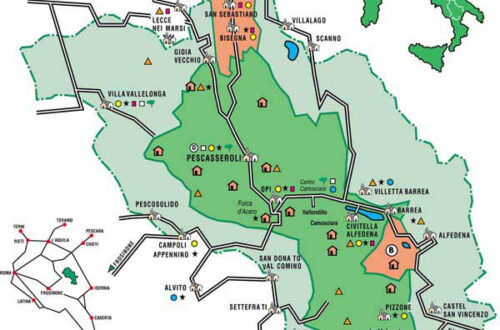

The tree will come from the Riserva Regionale Abetina di Rosello, which is considered one of the most important forests of the Appennines. Located on the border between Abruzzo and Molise, L’Abetina di Rosello and the adjacent forest of Pescopennataro preserve an almost intact strip of mixed forest of pine, white spruce, beech, yew and maple trees (including the very rare Lobel maple tree) as well as other species. Orchids are present in the undergrowth. It was in this area where Italy’s two tallest trees were found, each reaching over 50 meters in height.

The Rosello Nature Reserve was established by regional law in 1997, so this year marks its 25th anniversary. It is included in the areas protected by the European Union as a special area of conservation for the presence of species and habitats of community importance.

Rosello is proud to provide the Vatican Christmas Tree in 2022. The oasis which protects the forest is crossed by a deep gorge cut out by the Turcano river, and also protects numerous animal species, such as the wolf, the wild cat, the roe deer and the spectacled salamander. Birds such as black woodpeckers, hawks and wood pigeons also live in the forest.

What makes the Rosello forest one of the most important local reserves is the presence of fir trees. The fir trees of central Italy are different from the Alpine ones, since they have developed the ability to adapt to warm summer temperatures.

Ennio said the news about the Christmas tree from the Rosello forest brought back fond memories of when he was growing up in that town. He recalled that city hall would allocate a certain amount of wood to each family according to the size of the family. Then each family would take the wood from the felled trees to their home to help them stay warm in the winter. Ennio said when he was a boy, he would always help his father, who was a farmer and blacksmith and who would bring the wood by horse to their home, where Ennio would help unload it.

November/December 2022