-

Barisciano

By Nancy DeSanti

View of the Castle of Barisciano

Credit: WikipediaProvince of L’Aquila, Region of Abruzzo

The town is situated just below Monte della Selva on the southern side of the Gran Sasso. The surrounding countryside is rich in herbs such as thyme, helicrysus, and pharmaceutical issopus.

On this site was a Roman settlement, as indicated by the remains of Via Claudia Nova and the nearby Forfona archaeological area. Founded between the 5th and 7th centuries A.D., the town expanded, absorbing the surrounding areas of Villa San Basilio, Bariscianello, and Santa Maria di Forfona. Eventuallly, Barisciano took part in the foundation of L’Aquila.

In 1380, the town was invaded by Amatrice troops and in 1424, it was besieged by condottiere (leader of a troop of mercenaries) Braccio da Montone and subsequently surrendered. The women of the town were taken to L’Aquila with their breasts bare to humiliate them. But the length of time the feared condottiere spent fighting at Barisciano gave the city of L’Aquila the chance to reorganize and finally defeat him.

The town is most noted for the Castle of Barisciano which is a medieval fortress that was built on top of the Selva mountain. The fortress was constructed sometime during the 8th century in a key location on the Navelli plateau, with access to the Gran Sasso d’Italia. It was expanded into an enclosed fortress in the 13th century to house the populace in case of danger.

The condottiere Braccio da Montone stormed the fortress and destroyed it in 1424, while that city was under siege. The stronghold had contributed to the establishment of L’Aquila, and it remained a part of L’Aquila until 1529, at which point it became an aristocratic family fief. It was abandoned after it lost its defensive use in the 16th century.

The Chapel of San Rocco, which is home to the saint’s wooden statue and some paintings, was constructed next to one of the castle towers as a memorial to the plague that occurred in 1526. The rectangular-shaped castle enclosure has a one-kilometer circumference. There were eight towers total, with the primary pentagonal tower situated at the highest apex and the remaining towers distributed along the walls. Even though not occupied on a long-term basis like the castle, remnants of additional buildings are inside the walls.

Barisciano is noted for its floricultural research center located in the Monastery of San Colombo. The town is also known for its potato festival and donkey race (sagra delle patate con il palo degli asini) held every August.

What to See

- Monastery of San Colombo, which is now a floriculture research center

- Remains of the medieval castle guarding the Piana di Navelli on the one side and the road to Gran Sasso on the other

- Church of Santissima Trinità

- Church of Santa Maria di Capo di Serra from the 14th century

- Church of Santa Maria di Valleverde.

- Chapel of San Rocco

Important Dates

- August — Potato festival with a traditional donkey race (palio degli asini)

- November 25 — Feast of Santa Caterina

Italiano

Tradotto da Ennio Di Tullio

Provincia dell’Aquila, Regione Abruzzo

La bellissima cittadina di Barisciano si trova nel Parco Nazionale del Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga. Ha circa 1.828 abitanti, detti Bariscianesi.

Il paese è situato appena sotto il Monte della Selva, sul versante meridionale del Gran Sasso. La campagna circostante è ricca di erbe aromatiche come il timo, l’elicriso, e l’isopo farmaceutico.

In questo sito era presente un insediamento romano, come indicano i resti della Via Claudia Nova e della vicina area archeologica di Forfona. Fondato tra il V e il VII secolo d.C., il paese si espanse inglobando le aree circostanti di Villa San Basilio, Bariscianello, e Santa Maria di Forfona. Barisciano partecipò infine alla fondazione dell’Aquila.

Nel 1380 il paese fu invaso dalle truppe di Amatrice e nel 1424 fu assediato dal condottiero Braccio da Montone e successivamente si arrese. Le donne del paese venivano portate a L’Aquila a seno scoperto per umiliarle. Ma il periodo di tempo trascorso dal temuto condottiero combattendo a Barisciano diede alla città dell’Aquila la possibilità di riorganizzarsi e infine sconfiggerlo.

La città è nota soprattutto per il Castello di Barisciano, una fortezza medievale costruita sulla cima del monte Selva. La fortezza fu costruita durante l’VIII secolo in una posizione chiave sull’altopiano di Navelli, con accesso al Gran Sasso d’Italia. Nel XIII secolo fu ampliato fino a diventare una fortezza recintata per ospitare la popolazione in caso di pericolo.

Il condottiero Braccio da Montone esplose la fortezza e la distrusse nel 1424, mentre la città era sotto assedio. La roccaforte aveva contribuito alla fondazione dell’Aquila, della quale rimase fino al 1529 quando fu feudo di una famiglia aristocratica. Fu abbandonato dopo perse la sua funzione difensiva nel XVI secolo.

La Cappella di San Rocco, che conserva la statua lignea del santo e alcuni dipinti, fu costruita accanto a una delle torri del castello in memoria della peste avvenuta nel 1526. Il recinto del castello, di forma rettangolare, ha una circonferenza di un chilometro. C’erano otto torri in totale, con la torre pentagonale primaria situata all’apice più alto e le restanti torri distribuite lungo le mura. Anche se non furono occupati a lungo termine come il castello, ci sono resti di edifici aggiuntivi all’interno delle mura.

Barisciano è noto per il suo Centro ricerche floricole, situato nel Monastero di San Colombo. Il paese è noto anche per la sagra delle patate e la corsa degli asini (festival of the potatoes and the race of the donkeys) che si tiene ogni agosto.

Le attrazioni del luogo:

- Monastero di San Colombo, oggi centro di ricerca sulla floricoltura

- Resti del castello medievale, a guardia della Piana di Navelli da un lato e della strada per il Gran Sasso dall’altro

- Chiesa della Santissima Trinità

- Chiesa di Santa Maria di Capo di Serra del XIV secolo

- Chiesa di Santa Maria di Valleverde.

- Cappella di San Rocco

Date da ricordare:

- Agosto — Sagra delle patate con tradizionale corsa degli asini (palio degli asini)

- 25 novembre — Festa di Santa Caterina

Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barisciano

https://www.italyheritage.com/regions/abruzzo/laquila/barisciano.htm

https://weirditaly.com/2022/10/25/castle-of-barisciano-laquila/

November/December 2023

-

Montemitro

By Nancy DeSanti

Panoramic of Montemitro.

Credit: Asia Palomba / csmonitor.com

Province of Campobasso, Region of Molise

Coat of arms of the Comune di Montemitro.

Credit: WikipediaThe small town of Montemitro is located in the province of Campobasso near the Trigno river. It has approximately 468 inhabitants, known as Montemitrani.

This town is one of the Molise centers founded by refugees from the Balkans. Montemitro was founded in 1461 by a Croatian community under the leadership of Giorgio Castriota Skanderberg. The population still speaks a Slavic dialect. Like Acquaviva Collecroce and San Felice del Molise, Montemitro is home to a community of Molisian Croatians, most of whom speak a particular Croatian dialect as well as Italian.

The patron saint of Montemitro is Santa Lucia, and the church dedicated to her is the Church of Santa Lucia Vergine e Martire. However, the town does not celebrate the feast of Santa Lucia on its customary date of December 13, but rather on the first and last Fridays of May. This honors the crossing of the Adriatic Sea to Italy in the 15th century by the ancestors of the town’s residents who are believed to have carried a statue of Santa Lucia with them, arriving in Italy on a Friday in May.

Built in the 1930s near Montemitro, The Chapel of Saint Lucy is where locals honor the oral legend that the first Croatian refugees arrived in the area one Friday in May hundreds of years ago.

Credit: Asia Palomba / csmonitor.comThe language of the three cities is considered an endangered diaspora language. Along with Acquaviva Collecroce and San Felice del Molise, the town of Montemitro is being studied by anthropologists and language specialists. The residents keep ancient traditions, like the hand-weaving of blankets and tablecloths, and have a deep devotion to Santa Lucia, their patron saint.

Roughly 1,000 people in the towns of Montemitro, San Felice, and Acquaviva Collecroce speak Slavomolisano — or na-našo (pronounced “na-nasho”) — a blend of ancient Croatian and the local Italian dialect of the Molise region.

Created from the blend of Italian culture and the language spoken by 15th-century Croatian refugees, na-našo, meaning “our way,” its associated traditions have been passed down for generations. But as the town’s population has dwindled over the years and Italian has overtaken na-našo as their primary language. That heritage is fading.

Older members of the community have mostly accepted the possibility that their language will die out within the next few decades. But others, particularly younger people, are determined to see their culture preserved. Even though they may not speak na-našo as fluently as their forebears, they are a driving force behind efforts to celebrate and conserve their blended heritage.

Interestingly, na-našo would never have existed if the Ottomans had not invaded the Balkan peninsula in the 1400s, driving thousands of refugees toward the coast of Croatia and eventually across the sea to Italy. By the end of the 15th century, hundreds had landed along Molise’s coast, according to Giovanni Piccoli, a native of Acquaviva and former professor of Latin, Italian, and history at local universities.

At that time, Montemitro, Acquaviva, and San Felice had been abandoned due to an earthquake in 1456. So “the feudal lords, desperate to repopulate their lands, invited the refugees to inhabit these abandoned towns,” said Piccoli. After arriving in Molise, these refugees mixed their language with the local one, creating na-našo, and married the cultural and religious practices they had brought with them with local traditions.

But that was centuries ago. Today, Montemitro, the town that is arguably the most active of the three when it comes to speaking na-našo is also the smallest. That may be because Montemitro was poorly connected and isolated, which allowed its people to preserve the language for a longer time, said Padre Angelo Giorgetta, a local parish priest.

Even today, Montemitro retains some of that rugged remoteness. The streets encircling the town are unpaved, and tall grass and wildflowers grow in abundance along the streets. The people of the towns coexist with the wild landscape, often making their living off the land as farmers.

This ancient town has a panoramic view of the surrounding valley from around almost every corner; street names are written in both Italian and na-našo; and a smattering of benches in main squares are painted in vibrant colors, with local sayings and poetry verses in Italian and na-našo handwritten across the slats.

The cultural associations of the three towns recently banded together to create an artistic residency for Croatian artists with the aim of valorizing their cultural heritage through art. And there are tentative plans to host an artistic residency several times a year to coincide with the towns’ cultural and religious events.

These cultural efforts have also stretched across the sea to involve Croatia. Three Croatian presidents have visited the towns, most recently in 2018, to acknowledge the link Molise and Croatia continue to share despite five centuries of change. In fact, Montemitro has been granted an Honorary Consulate by Croatia.

AMHS member Joann Novello noted that Montemitro is her late mother’s hometown, and the priest mentioned in the article, Padre Angelo Giorgetta, is her mother’s cousin’s son. He visited the Novellos here about 15 years ago.

What to See

- Church of Santa Lucia, with a 14th century portal

Important Dates

- First and Last Fridays of May — Feast of Santa Lucia, the patron saint

Italiano

Tradotto da Ennio Di Tullio

Provincia di Campobasso, Regione Molise

Il piccolo comune di Montemitro si trova in provincia di Campobasso nei pressi del fiume Trigno. Ha circa 468 abitanti, conosciuti come Montemitrani.

Questo è uno dei centri molisani fondati dai profughi provenienti dai Balcani. Fu fondata nel 1461 da una comunità croata sotto la guida di Giorgio Castriota Skanderberg. La popolazione parla ancora un dialetto slavo. Come Acquaviva Collecroce e San Felice del Molise, Montemitro ospita una comunità di croati molisani, la maggior parte dei quali oltre all’italiano parla un particolare dialetto croato.

La patrona di Montemitro è Santa Lucia, e la chiesa a lei dedicata è la Chiesa di Santa Lucia Vergine e Martire. Il paese però non celebra la festa di Santa Lucia nella data consueta 13 dicembre, bensì nel primo e nell’ultimo venerdì di maggio. Questo onora la traversata del Mar Adriatico verso l’Italia nel XV secolo da parte degli antenati degli abitanti della città che si ritiene abbiano portato con sé una statua di Santa Lucia, arrivando in Italia un venerdì di maggio.

La lingua delle tre città è considerata una lingua della diaspora in via di estinzione. Insieme ad Acquaviva Collecroce, e San Felice del Molise, il comune di Montemitro è oggetto di studio da parte di antropologi e specialisti del linguaggio. Gli abitanti conservano ancora antiche tradizioni, come la tessitura a mano di coperte e tovaglie, e hanno una profonda devozione per Santa Lucia, la loro santa patrona.

Circa 1.000 persone nelle città di Montemitro, San Felice, e Acquaviva Collecroce parlano lo slavomolisano — o na-našo (pronunciato “na-nasho”) — una miscela dell’antico croato e del dialetto italiano locale della regione Molise.

Creato dalla fusione della cultura italiana e della lingua parlata dai rifugiati croati del XV secolo, na-našo, che significa “la nostra via”, le sue tradizioni associate sono state tramandate da generazioni. Ma poiché la popolazione della città è diminuita nel corso degli anni e l’italiano ha superato il na-našo come lingua principale, quell’eredità sembrava vicina alla fine.

I membri più anziani della comunità hanno per lo più accettato la possibilità che la loro lingua si estinguerà entro i prossimi decenni. Ma altri, soprattutto i più giovani, sono determinati a vedere preservata la propria cultura. Anche se potrebbero non parlare na-našo così fluentemente come i loro antenati, sono una forza trainante negli sforzi per celebrare e conservare la loro eredità mista.

È interessante notare che na-našo non sarebbe mai esistito se gli Ottomani non avessero invaso la penisola balcanica nel 1400, spingendo migliaia di rifugiati verso la costa della Croazia e infine attraverso il mare verso l’Italia. Alla fine del XV secolo, centinaia erano sbarcati lungo le coste molisane, secondo Giovanni Piccoli, originario di Acquaviva ed ex-professore di latino, italiano, e storia nelle università locali.

A quel tempo Montemitro, Acquaviva, e San Felice erano stati abbandonati a causa del terremoto del 1456. Così “i feudatari, nel disperato tentativo di ripopolare le loro terre, invitarono i profughi ad abitare questi paesi abbandonati,” racconta Piccoli. Giunti in Molise, questi profughi mescolarono la loro lingua con quella locale, creando na-našo, e sposarono le pratiche culturali e religiose che avevano portato con sé con le tradizioni locali.

Ma questo accadeva secoli fa. Oggi Montemitro, il paese che è probabilmente il più attivo dei tre quando si tratta di parlare na-našo, è anche il più piccolo. Ciò potrebbe essere dovuto al fatto che Montemitro era poco collegato e isolato, il che ha permesso alla sua gente di preservare la lingua per un tempo più lungo, ha detto Padre Angelo Giorgetta, parroco locale.

Ancora oggi Montemitro conserva parte di quella aspra lontananza. Le strade che circondano la città non sono asfaltate e lungo le strade crescono erba alta e fiori di campo. La gente delle città convive con il paesaggio selvaggio, spesso guadagnandosi da vivere lavorando come agricoltori.

Questa antica città ha una vista panoramica sulla valle circostante da quasi ogni angolo; i nomi delle strade sono scritti sia in italiano che in na-našo; e un’infarinatura di panchine nelle piazze principali sono dipinte con colori vivaci, con detti locali e versi di poesie in italiano e na-našo scritti a mano sulle stecche.

Le associazioni culturali delle tre città si sono recentemente unite per creare una residenza artistica per artisti croati con l’obiettivo di valorizzare il loro patrimonio culturale attraverso l’arte. E ci sono piani provvisori per ospitare una residenza artistica più volte all’anno in concomitanza con gli eventi culturali e religiosi delle città.

Questi sforzi culturali si sono estesi anche oltre mare per coinvolgere la Croazia. Tre presidenti croati hanno visitato le città, l’ultima volta nel 2018, per riconoscere il legame che Molise e Croazia continuano a condividere nonostante cinque secoli di cambiamenti. Montemitro, infatti, ha ottenuto il Consolato Onorario dalla Croazia.

Il membro dell’AMHS Joann Novello ha notato che Montemitro è la città natale della sua defunta madre, e il sacerdote menzionato nell’articolo, Padre Angelo Giorgetta, è il figlio del cugino di sua madre. Ha visitato i Novello qui circa 15 anni fa.

Le attrazioni del luogo:

- Chiesa di Santa Lucia, con portale del XIV secolo

Date da ricordare:

- Primo e Ultimo Venerdì di Maggio — Festa di Santa Lucia, patrona

November/December 2023

-

Siamo Una Famiglia

Sunday Lunch Outing

Eighteen AMHS members, family and friends enjoyed savory Italian food for lunch at A Modo Mio (My Way) in Arlington, Va., on Sunday, October 1, 2023. A Modo Mio is recognized as one of the best pizzerias in the area.

Credit: Courtesy of Maria D’Andrea-YothersAMHS Represented at Columbus Day Ceremony

Board member Teresa M. Talierco and AMHS member Joseph Scafetta III presented a wreath during the October 9 Columbus Day ceremony on behalf of our society at the explorer’s statue in front of Union Station in Washington, D.C.

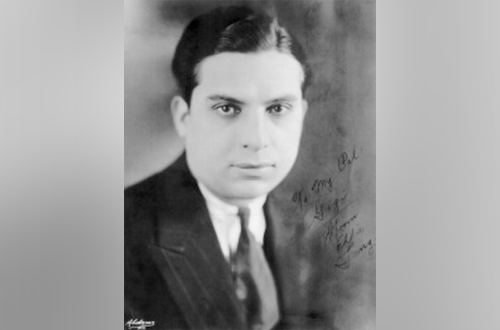

Credit: Michael GeringMemorial Mass for Father Peter Paul Polo

Father Peter Paul Polo, the former Holy Rosary pastor who died in Italy last month, was remembered at a memorial Mass in the church on September 16, 2023.

Father Polo passed away on September 13 at the Scalibrian retirement home in Bassano del Grappa. He was the pastor at Holy Rosary from 2021 to 2022. During the memorial Mass, Father Walter Tonelloto, the current pastor, recalled knowing Father Polo since they were seminarians together, and he noted that their families had been friends since that time. He told parishioners that one of Father Polo’s last messages was that he felt “gratitude” for the life he led.

Father Polo was a supporter of AMHS during the time he was at Holy Rosary, and he attended our programs during that period. He served on the Provincial and General Councils of the Scalabrinian order in Rome and in parishes in New York and New England before coming to Washington, D.C.

Fr. Peter Paul Polo

Credit: Courtesy of Maria MariglianoItalian Wounded Warriors Honored

On September 17, 2023, a Mass was held at Holy Rosary Church to honor a group of Italian Wounded Warriors, and a reception was held afterwards in Casa Italiana. A military delegation from the Embassy of Italy also attended.

The reception was organized by AMHS member Maria Marigliano and her sister Giovanna. Several AMHS members had the opportunity to greet the wounded veterans.

Italian Wounded Warriors and community members at the reception in their honor.

Credit: Courtesy of Ennio Di TullioBucket List Item Completed, Mount Everest Base Camp (EBC)

AMHS member Sam Yothers and his daughter Lauren recently completed a 20-day expedition in Nepal. Here Sam celebrates standing on the actual EBC glacier with Mount Everest peaking above her supporting mountains. To the bottom left, you can see the dangerous Khumbu Icefall where intrepid climbers begin their summit ascent.

Credit: Lauren YothersKeep Up with AMHS Events The Society sends regular emails to our members alerting them of upcoming events, although we promise not to send too many. Please check your inbox weekly to see what is in the works so you may join in the fun. November/December 2023

-

AMHS Membership

By Lynn Sorbara, 2nd Vice President-Membership

New Members Welcome to our New Members: Giorgio Consolati Birthdays Compleanni a Novembre

Eileen Verna and Naomi Leibold, November 1; Rev. John V. DiBacco, Jr., November 2; Richard Durkin, November 3; Rita Carrier and Michael DeBonis, November 4; Elena Biondi, November 5: Sergio Fresco, November 8; Joe Ruzzi, Jr., November 9; Michael McDonald, November 10; Clara Cuonzo, November 14; Emilia DeMeo, November 12; Edvige D’Andrea, Joseph D’Andrea, and Dena DeBonis, November 19; William DiGiovanni, November 21; Christina Iovino, November 25; Norma Phillips, November 29; and Amelia DiFiore, November 30.Compleanni a Dicembre

Rosalie Ciccotelli, December 2; Domenica Marchetti, December 3; Alfred Del Grosso, December 4; Marlene Lucian and Louie Anne D’Ottavio, December 6; Frank Bonsiero, December 8; Stephen di Girolamo, December 9; Stephanie Salvagno Frye, December 10; Donna DeBlasio, December 11; William Lepore and Barbara Gentile, December 12; Maria D’Andrea-Yothers, December 13; Cathy Branciaroli, December 16; Domenico Conti, December 18; Elodia D’Onofrio and Carmine James Spellane, December 20; Anna Isgro’, December 21; Claire DeMarco, December 22; Brian Pasquino, December 25; Michael Savino, and Annie Thompson, December 26; and Margot DeRuvo Gilberg, December 29.Anniversaries Anniversari a Novembre

Harry & Joan Piccariello, November 9.Anniversari a Dicembre

Ray & Michele LaVerghetta, December 11; and David & Cristina Scalzitti, December 27.Membership Information Category # of Persons

Associate (Couple): 2 x 2 = 4

Associate (Individual): 33

General (Couple): 45 x 2 = 90

General (Individual): 76

Honorary: 9

Scholarship: 2

Student: 5

Total Membership: 219

November/December 2023