How Six Immigrant Brothers Left Their Mark On American Cities

By Nancy DeSanti, 1st Vice President—Programs

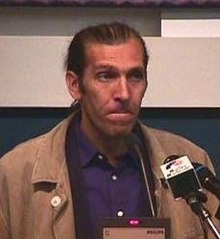

John Belardo (at lectern) gave a presentation on the work of the Piccirilli brothers to assembled AMHS members and guests on May 19.

Credit: Carmine James Spellane

Most Americans are not aware of the many masterpieces of the Piccirilli brothers, but AMHS members and guests at a recent program at Casa Italiana had the opportunity to learn a great deal about them from John Belardo, an accomplished sculptor from New York City. Belardo is an expert on the six famous Italian immigrant brothers who had a hand in some of the most important and famous sculptures we have both in Washington, D.C., and in New York City.

The AMHS program on Sunday, May 19, 2024, was co-sponsored by the Casa Italiana Sociocultural Center. Among the attendees were Steven Livengood, the Public Historian for the U.S. Capitol Historical Society, and Davide Prete, an Italian sculptor from Treviso, now living in Washington. He donated two of his works to the Italian-American Museum of Washington, D.C.

Belardo became interested in the marble carvings and sculptures of the Piccirilli brothers while he was a teacher in the Bronx, not too far from the building where the brothers set up their studio after emigrating from the Tuscan province of Massa-Carrara in 1888, first settling in Manhattan. They ended up in the Bronx, about 20 blocks from where Yankee Stadium is now located, after their mother became ill and the doctor advised her to “move to the country.” It is hard for us today to imagine that back then the Bronx was considered the country!

Belardo was educated as a sculptor at the New York Academy of Art and has been a visiting scholar for the Institute for American Universities. His work is wide ranging, from monumental public installations to digital prototypes and designs, as well as large-scale ceramic sculptures. He was recently the Artist in Residence at Chesterwood, which is the historic home of Daniel Chester French, the designer of the Lincoln Memorial. Belardo’s work is permanently installed at Georgetown University, Cooperstown N.Y., and Lehman College CUNY, where he currently teaches. He recently presented a talk, “Piccirilli Studio,” at the annual conference of the National Sculpture Society.

According to Belardo, among the six talented Piccirilli brothers—Ferruccio, Attilio, Furio, Masaniello, Orazio, and Getulio–the most accomplished was Attilio. The brothers learned from their father Giuseppe, who himself came from a long line of stone carvers. While the brothers were known primarily as architectural modelers and carvers of other sculptors’ works, Attilio and Furio further distinguished themselves as sculptors in their own right.

Belardo noted that the brothers were known for treating their workers well, and at one point their workers numbered up to 100.

Not surprisingly, the brothers’ talent was quickly recognized, and artists from all over the country came to their studio. At that time, most prominent sculptors created their original work in clay. From that clay model, a caster generated a plaster model. The plaster model was then sent to the Piccirilli brothers who carved it in stone, usually marble. As Belardo pointed out, if you make a mistake working with clay, it can be fixed, but not so with stone and marble. Soon, well-known designers, such as Daniel Chester French, called on the brothers to help to execute the “city beautiful” idea of transforming American cities to look like the grand cities of Europe.

The Piccirillis did much to beautify New York City, including the original pediment of the New York Stock Exchange, and their carvings are exhibited in the atrium of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Perhaps their best-known works there are the magnificent lions flanking the entrance to the New York City Public Library.

In Washington, their best-known work is the colossal Lincoln statue which was designed by Daniel Chester French and unveiled in 1922. The 28 separate blocks were shipped from their Bronx studio and put together here inside the Lincoln Memorial.

Another one of their projects in Washington was the beautiful DuPont Circle fountain, which has three allegorical figures representing modes of navigation by the sea, the stars, and the wind. The figures are very fitting, since the fountain is named after Rear Admiral Samuel DuPont.

The last of Attilio’s public commissions was the Guglielmo Marconi statue located outside a public library at 16th & Lamont Streets, N.W., in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of D.C. It was dedicated in 1941. The sculpture features two bronze pieces. In the front, there is a bust of Marconi while the second bronze is an allegorical female figure sitting on a globe. It is a fine tribute to the great inventor whose 150th birthday anniversary is being celebrated this year.

Belardo summarized the Piccirilli style as embodying simplicity, beauty, and elegance. To pass on their knowledge, Attilio established the Leonardo da Vinci Art School for impoverished, mostly immigrant students who could not afford regular tuition and who attended school mostly at night, after work. Unfortunately, the school closed during World War II. Not long afterwards, a fire damaged the studio, including their historical records.

Washington, D.C., and New York City owe a debt of gratitude for the legacy which the brothers left in the cities that they beautified.

Our sincerest thanks to our speaker John Belardo for making the trip from New York City with his son Joseph at their own expense. Also, many thanks to Peter Bell for delivering the delicious lunch from A. Litteri’s, and to those members who donated raffle prizes and bought tickets.

June 2024